Remembering “Soakie’s”: Kansas City’s former Black gay bar from the Y2K Era

Volume_2 of {B/qKC}, rediscovers Soakie’s: a former Black gay bar in Kansas City from 1994-2004. A refurbished version of the groundbreaking article for {B/qKC}’s database.

BY NASIR MONTALVO ● ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE KANSAS CITY DEFENDER ON DECEMBER 22, 2023

Foreword

Welcome to Volume_2 of {B/qKC}. It would be remiss for me to begin this new era without saying thank you. Though I believe it is the inherent duty of any human being to understand the place and time they reside in, I am deeply touched by the many hands contributing to this communal archival project. I thank those who offered space, those who offered capital, those who offered affirmation, those who offered critique, those who offered love, and–above all–those Black queer Kansas Citians who believed so deeply in their liberation that we can, now, continue their work.

Since Volume_1’s completion earlier this Summer, I have been working intensely and intently on expanding {B/qKC}. The project initially grew from a frustration with the lack of Black queer spaces in Kansas City, and I, thus, saw a need to investigate the history of Black queer people in our city. Volume_1 was focused on “liberating” Black queer photos, documents and ephemera from local institutions that had no plans to widely publish the materials or make them digitally accessible.

Volume_2 and all forthcoming installments will be dedicated to building one of the world’s only Black queer archives.

Volume_2 launches with three collections from our local Black queer eldership, each telling its own story of Soakie’s: a Black gay bar that served as the birthplace for many of our local Black queer elders today.

There are many goals I hope to accomplish with {B/qKC}, but the project’s main tenets are to:

1) increase access to our Black, queer Kansas Citian histories, 2) challenge local institutions and the concept of “ownership,” 3) demonstrate precedence for future reparative efforts, and 4) educate and imagine Black queer futures through community reflection of this historical research.

With bigoted legislation and representation that actively seeks to erase our knowledge and indoctrinate future generations, it is more important than ever to document our histories-not just as static stories but as didactic, interactive artifacts that educate, challenge, storytell, pay homage, repair, destroy, and build anew.

At its very core, aside from the archive’s historical content, I am using {B/qKC} to create new ways to engage with our City’s contentious past-in a way that doesn’t center worship of written word, paternalism, and objectivity (characteristics of “white supremacy culture” coined by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun). Instead, I want to challenge us to learn history through conversation and community, working in unconventional spaces, not just the white, sanitized institutional settings we are told to.

Considering {B/qKC}’s historical content with the aforementioned objectives, the project grows beyond an archive, it is a tool for abolition: the project is dismantling the ways we traditionally engage with history, while paying homage to Black queer folk-literally, through dollars, and figuratively, through remembrance. And as I want this research to bring in subjectivity and analysis, {B/qKC} also examines what ways we’ve succeeded and what ways we’ve failed to keep Black queer folks safe-and what must be done moving forward so that these missteps won’t happen again (or, at the very least, are rectified).

Volume 2 begins with Soakie’s. Outcast from their age’s existing spaces, Black queer Kansas Citians found solace in a Downtown Kansas City sandwich shop–converging at night for drinks, music, performances, and community. We learn how white people and capitalism ultimately led to both the creation and downfall of Soakie’s, and why there are currently no Black gay bars in Kansas City.

This is a lesson in the enduring fight to divest from white capital and how physical space has contributed to Black liberation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to expressly thank Gary Carrington, Craig Lovingood and Starla Carr for being {B/qKC}’s inaugural archive donors. Not only have they been instrumental in developing this article, they have also shown me love and welcomed my presence with open arms.

I would also like to thank Jerry Colston, Eric Robinson, Baby Boi, and Korea Kelly for taking time to speak with me and being warm, loving advocates of Black queer Kansas City’s pasts, presents and futures.

I’d also like to thank Zharee Richards, DuJaun Kirk, and Julia Soondar for being grounding relationships outside of this project. I’d also like to thank my newfound brother, Christopher, for reminding me that family is everywhere.

And finally, I’d like to thank the Universe for her guidance and my canine child, Guapo.

Copyright & Takedown Notice

{B/qKC} is making this content available for educational and research purposes. The Defender has obtained the needed permissions from various copyright holders for the use of this material and presents the majority of this material under a licensing agreement as part of {B/qKC}-unless otherwise noted.

{B/qKC} does not own any of this licensed content, and none of these works are in the public domain. Permissions to reproduce any of this material must be obtained from the copyright holder. You are responsible for obtaining written permission from the copyright owners of materials not in the public domain for distribution, reproduction, or other use of protected items beyond educational and personal use. If you would like to use the materials for screenings, remixes, or any other project please contact us and we will do our best to collaborate with you or put you in contact with the owners. For any inquiries, please email 1800nasi@tutamail.com and include links to all the material you wish to reference.

If you are the copyright holder and feel for any reason that your work has been presented on this page without your consent, please email 1800nasi@tutamail.com to request the removal from this site.

Vol_2 of {B/qKC}: Soakie’s

“After everything is said and done, Soakies was home.”

— Baby Boi, 2023

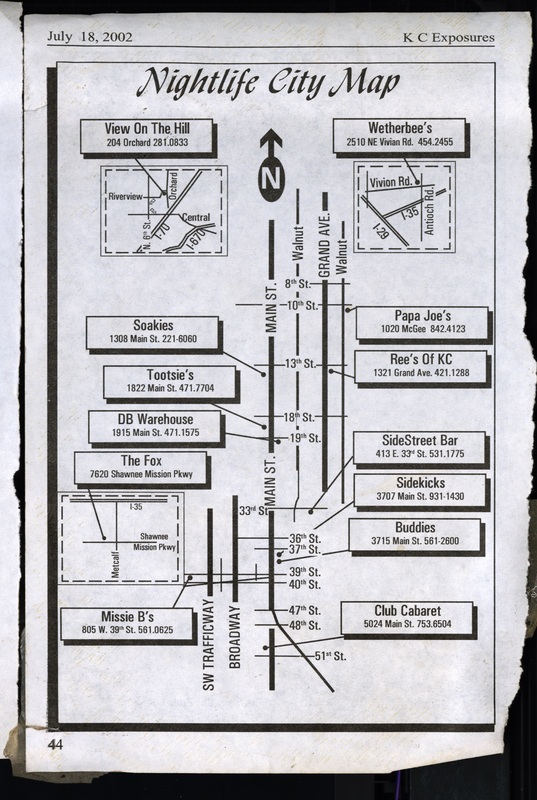

In Kansas City circa July 2002, you could stumble upon one of a whopping 13 gay bars and clubs; 8 of these lived on Main Street–including Sidestreet and Sidekicks, names that some may be familiar with today (see Figure 1).

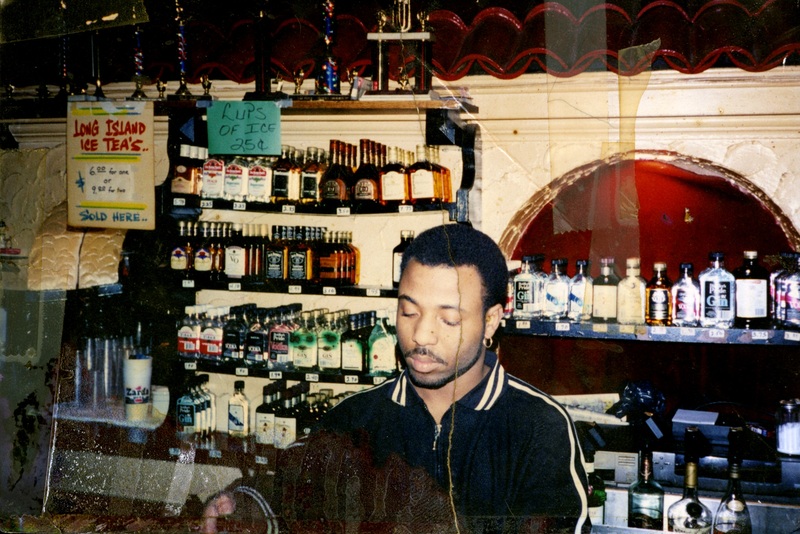

Lesser-known of that bunch is Soakie’s; the once “Famous for Sandwiches” spot operated by Italian mobsters was also one of Kansas City’s, and the world’s, few Black gay bars from 1994-2004.

Now there are only 8 gay bars in Kansas City, and a good chunk of these are plagued with accusations of racism, transphobia, femmephobia and lesbophobia.

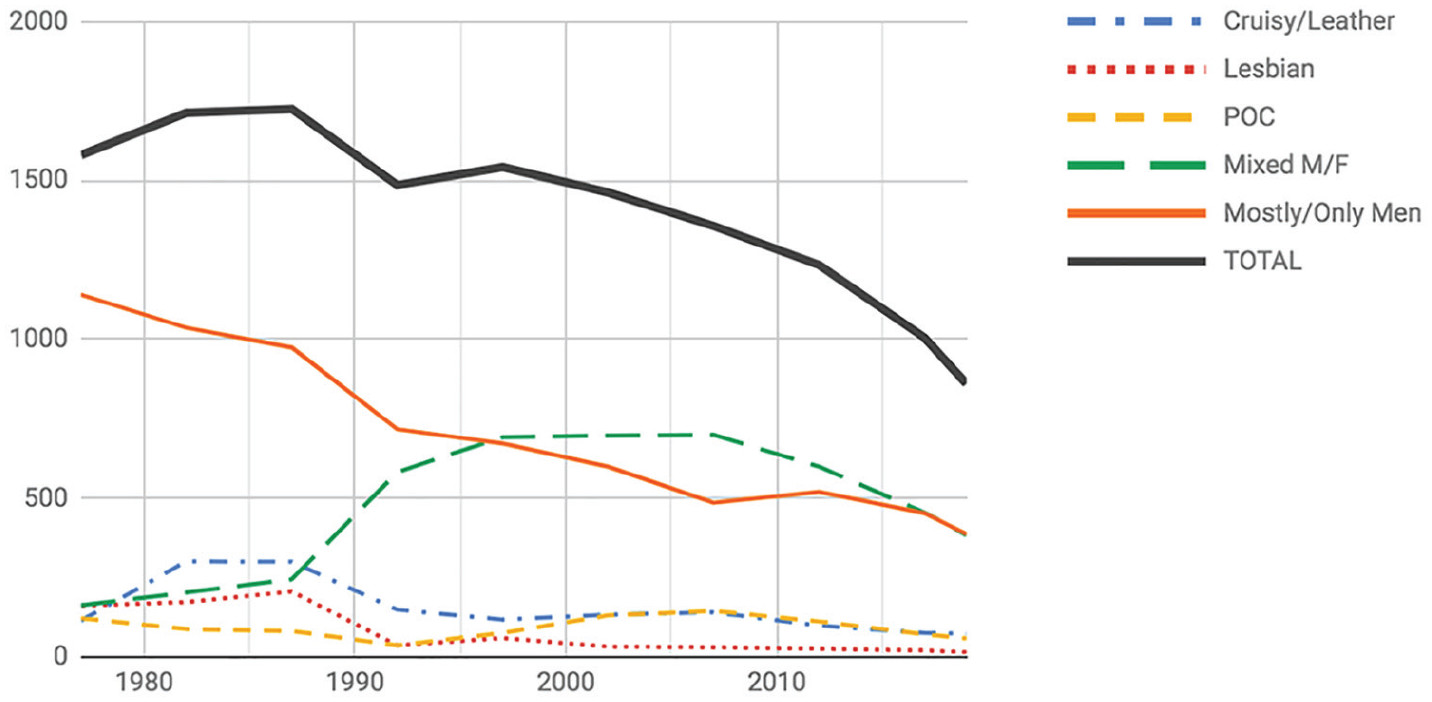

According to a 2019 study by Greggor Mattson1, a professor of Sociology at Oberlin College, Mattons infers, based on the annual Damron guides, that LGBTQ+ bars have been on a steep decline since the 1980s (see Figure 2). From 2007 to 2019, LGBTQ+ bars as a whole declined by 36.6% while queer bars for people of color declined by nearly 60%.

In short, we are losing our safe spaces.

There has recently been a shift in the neo-liberal sphere where, instead of using the term “safe spaces,” they express the need to be fostering “brave spaces.” The idea is that brave spaces honor discomfort and, thus, the expensing of emotional labor as a means for growth. While I get the sentiment, this is something that white people need to create for themselves, and in addition to the spaces Black queer people need exclusively for themselves.

When night rolls around and people retire to friends and cocktails at their favorite places, where can Black queer Kansas Citians go and truly feel celebrated and safe?

The answer is nowhere–at least, not above ground.

And this is why it is so important to share the story of Soakie’s: a public beacon of kinship for Black queer Kansas Citians and the gay awakening for much of our Black queer eldership today.

Soakie’s: The Sandwich Bar

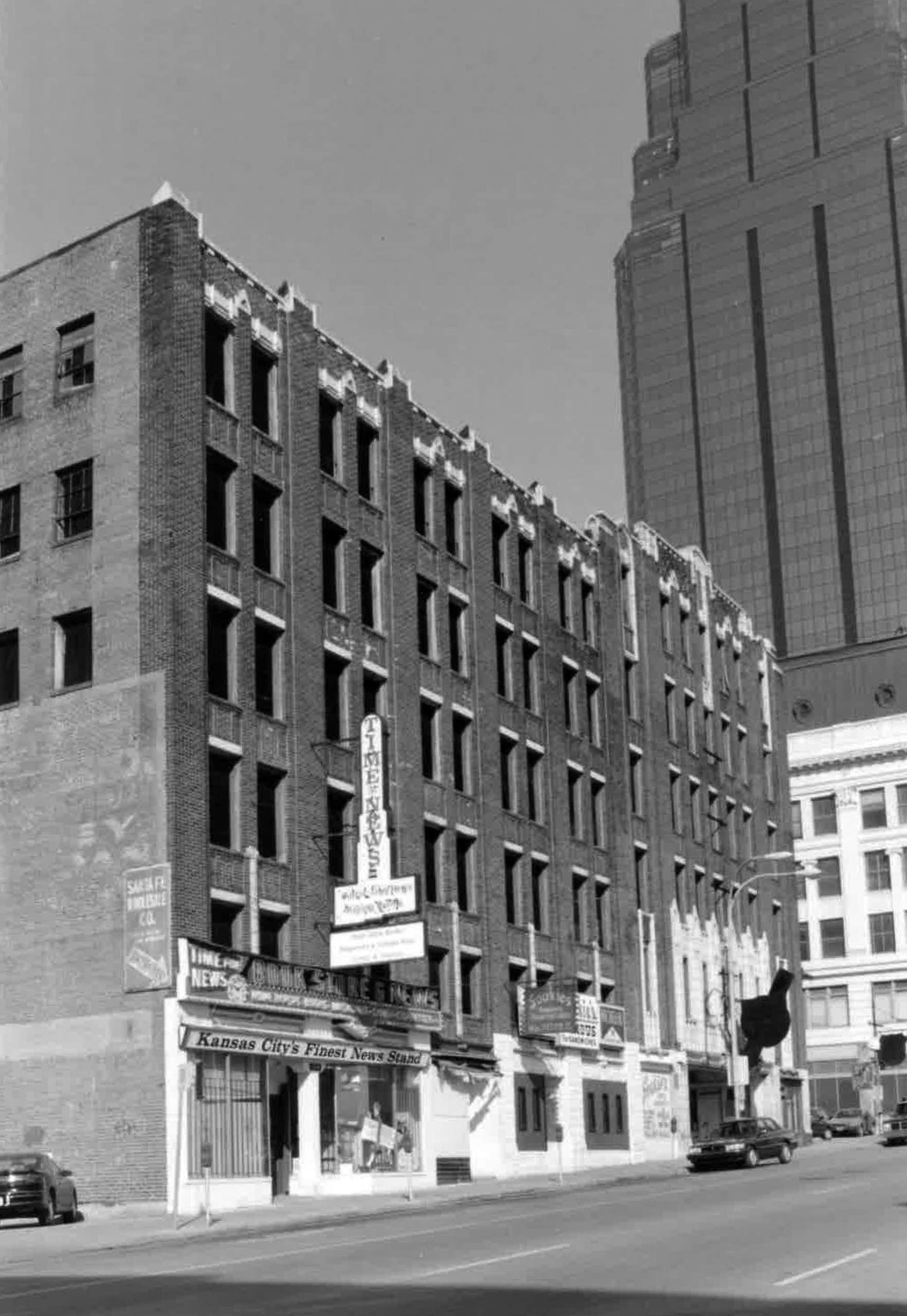

Founded by Italian mobster Salvatore A. “Soakie” Rinaldo in 1962, Soakie’s initially started out as a local neighborhood dive bar at 1308 Main Street–roughly, where Yard House is located today4. Though Rinaldo was notorious in Kansas City as part of the mob, not much else is known about his personal or family life due to general fear around mob culture.

Soakie’s functioned primarily as a packaged liquor and sandwich shop, recognizable by its sign’s slogan “Famous For Sandwiches;” the bar also cashed checks for those who didn’t have bank accounts or didn’t want the hassle of making an extra trip to the bank5. According to an early 2000’s internet chat room, the sandwiches were delectable, and many downtown workers frequented there during their lunch time6.

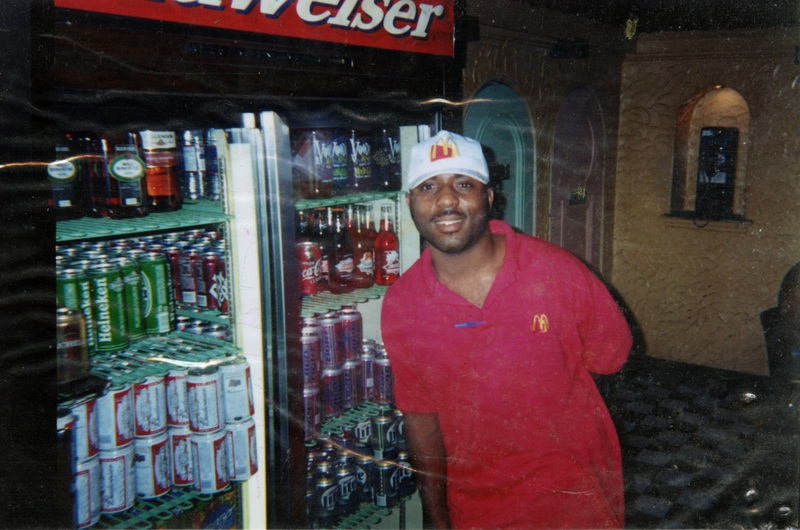

The space was small, and functioned as a dive bar–it had no more than a few high top tables, a jukebox, a pool table, and a small upstairs area that would eventually turn into a dance floor that could house 50 people. It was housed right next to a parking garage and across from a parking lot.

But that didn’t stop the bar from becoming a popular hangout spot for Black queer Kansas Citians. Because of the jukebox and its proximity to another gay hotspot, Connections (now known to many as Sidekicks), many Black queer locals would go to Soakie’s to pregame.

Soakie’s: The Black Gay Bar

Before local Black queers found community at Soakie’s in 1994, people had to make do with white gay clubs that weren’t receptive or welcoming to Black folks.

White gay clubs are historically accused of having racial quotas and requiring multiple forms of identification from Black people to limit their numbers within the establishment; the famed Dixie Belle Bar (another gay bar in Kansas City) was one of these. Located on 1922-1924 Main Street, the bar would come under fire for its racist practices, including the display of a Confederate Flag-prompting a local, interracial gay organizing group to condemn their actions7.

Jerry Colston, a prominent figure in Soakie’s rebirth as a nightclub, recounts his experience there in the 1990s:

"A couple people used to tell me, 'Why you go down there, don't you know that they don't care about you?' Where else am I gonna go? Your house? I mean, you know, where else am I supposed to go? We don't have nowhere to go."

It was this same sentiment that would lead Colston and his good friend Eric Robinson to pitch a new idea to Salvatore A. Rinaldo to transform his sandwich bar into a nightclub. 8

That Fateful Meeting

According to Colston and Robinson, Rinaldo was getting ready to close his shop around the same time Soakie’s was becoming a pregame spot for Black queer people in the ’90s. The three of them had established a friendly rapport in light of this. In fact, Robinson notes that Rinaldo treated him and the community with kindness and was extremely supportive.

“We don't have nowhere to go.”

— Jerry Colston, 2023

Over the course of a few months, as Rinaldo spoke of hardship with the bar, Colston and Robinson pitched various ideas that eventually led them to propose a full business plan-Soakie’s could turn into a nightclub on weekends.

Rinaldo approved, but would not invest in the concept. So, Colston and Robinson began funding the club’s necessities from scratch–adding things like a DJ booth (and the equipment needed for it) and stretching the club’s tight space by using a curtain that extended to the entrance of the next-door parking garage. They’d also paint the front of Soakie’s in its signature white and blue colors.

From there, the duo marketed the new club through word-of-mouth and by hustling flyers. They already had their names out in the community, which helped draw in big crowds.

The first night of the club’s opening, there was a line wrapped around the block.

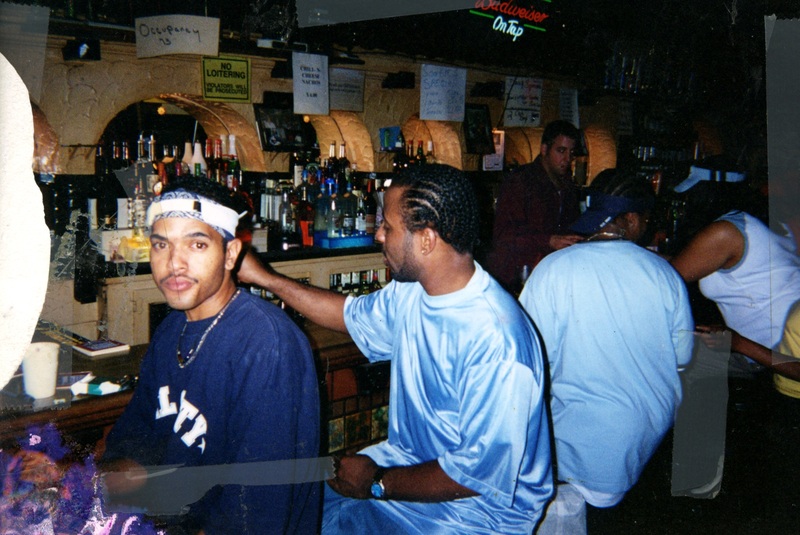

Views of Soakie’s Interior

A birthplace for Black queer identity

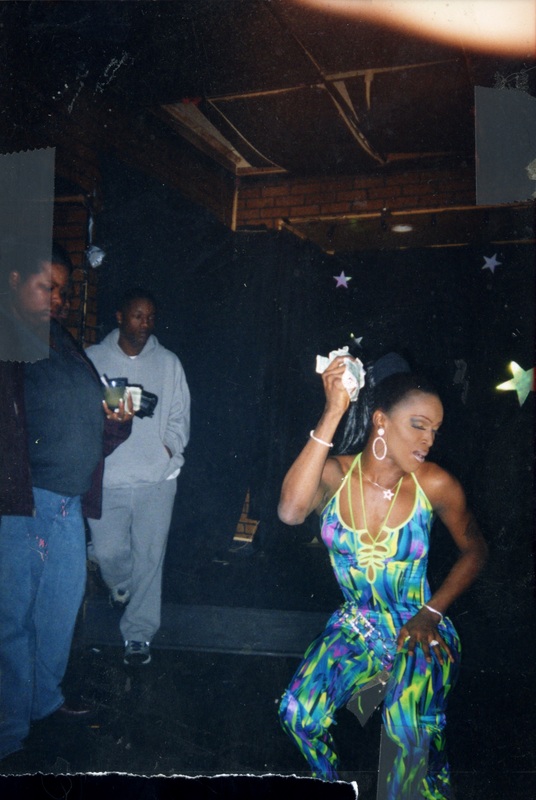

From then on, the Black gay nightclub would open Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Though primarily a club, where Soakie’s truly shined were in its performers.

Because Soakie’s was so intensely tied to Kansas City’s underground ballroom scene, it became host to a multitude of entertainers and different events: competitions, pageants, birthdays and more. This also meant more people became involved with managing the bar and its events–namely Tisha Taylor and Gary Carrington, a local Black drag queen and performer/emcee, respectively, and both legends in their own right.

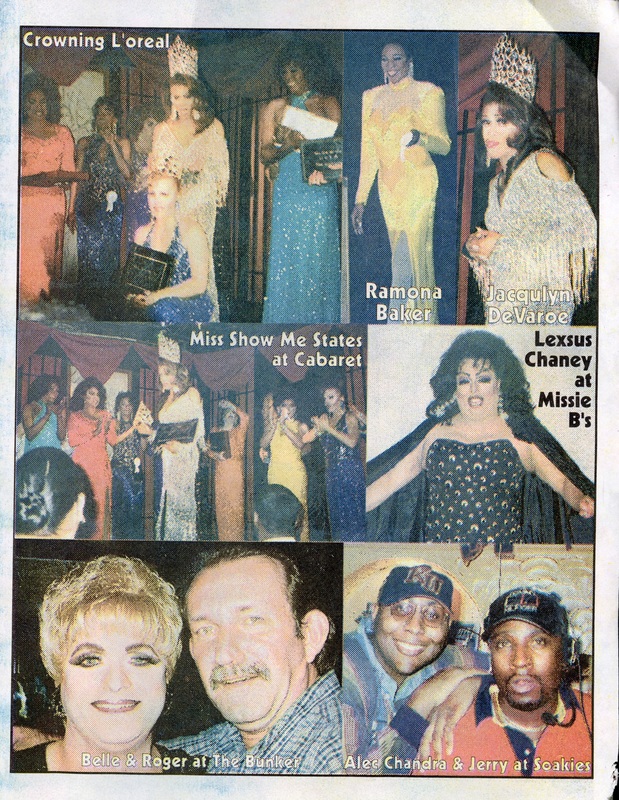

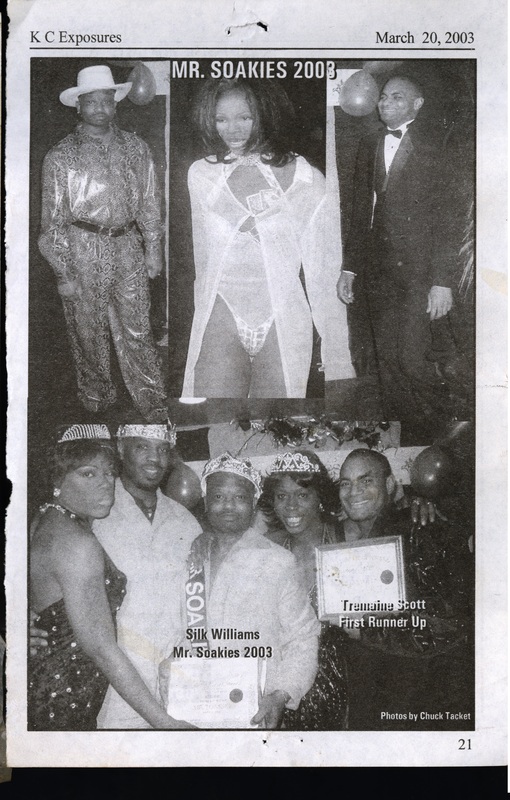

One of Soakie’s most noteworthy events, covered in several editions of KC Exposures, a former, local LGBTQIA2S+ weekly publication of the period, was “Mr. and Miss Soakies.” The event was a summer pageant competition to crown the eponymous king and queen of the bar. The competition was based on evening wear, talent and an interview–similar to a beauty competition. Winners would receive a trophy, plaque, sash, flowers and a cash prize.

Other noteworthy competitions included:

- The Lords & Ladies Pageant: a pageant for Black masc (‘Lords’) and femme (‘Ladies’) lesbians

- Mr. & Miss Black Gay Pride: a pageant coinciding with Kansas City’s annual Black Pride in August

When the bar began declining around the early 00s, Tisha Taylor created “Taylor Time”: a raffling event on Sundays where folks could buy a drink and enter into a drawing for a multitude of prizes–one time even including a car.9Tisha notes that it drew in straight crowds and critical funding for the bar. And as a rule instituted by Tisha, folks would have to exclaim “Right here, honey!” to claim their prize if their number was called.

Although Soakie’s was brimming with Black queer joy, members note that the bar wasn’t free of controversy. Gary Carrington chronicles how Soakie’s value as a safe space was threatened:

"We got a lot of pushback when we first started growing. We got a lot of 'spies' who would pop-up and come in. They'd order a drink, not finish it, and then leave."

A lot of vitriol also came as a result of John Koop, known by their drag name Flo, who was the creator of Show Me Pride, LLC–a business that began running Kansas City’s annual Pride in 2003, shifting the parade from a protest to a capitalist spectacle. Flo was expressly named as a racist by a multitude of Black LGBTQIA2S+ Kansas Citians during my research; she would commonly discourage people from attending Soakie’s by using the bar as a punchline during her shows at Missie B’s.

The Soakie’s staff, however, was extremely protective of attendees at the bar–Starla Carr, a founder of Kansas City’s drag king circuit in the 2000s, mentions how, although it has become a running joke now, a baseball bat was kept underneath the bar at all times. Starla also recognized that aside from being a patron and performer, she was also a gatekeeper.

More about John Koop and historic racism in Kansas City's queer community can be read in "The Unseen Struggles: Erasure and Racial Inequities in Kansas City's Queer Community" originally published in the Urban League of Greater Kansas City's 2023 State of Black Kansas City report.

Parkin’ Lot Pimpin†

Famously referenced by local Black queers, one of the most critical components of Soakie’s existed outside the bar.

Across 1308 Main Street was a large parking lot that became a hangout spot for Black queer people. Audiences in the lot differed: Korea Kelly (a local legend), Starla Carr and DJ Baby Boi speak about it being an entrypoint into learning more about their identities, as they were all too young to enter the bar at the time. It was a spot for after hours hangouts and people who couldn’t afford cover charges. People even walked pageants and competitions in the lot. To an extent, it became a destination as much as Soakie’s itself.

This would become an issue, though, as it drew away from the capital Soakie’s owners were receiving, and was also the source of a lot of violence.

† There are currently no photos available in the public domain, or as donated to {B/qKC}, that capture festivities in the parking lot across from Soakie's. If you are in possession of any relevant photographs or material and would like to contribute to this article (and archive, overall) please contact Nasir Montalvo.

The People of Soakie’s

In my interviews with a long list of Black queer people who used to attend Soakie’s, they unanimously noted that Soakie’s was the birthplace of their fully-formed identities–a place where they first embodied their queerness.

Below are a few Black Kansas Citians who were involved with Soakie’s in some way–including those who have graciously donated to the inaugural digital collections of {B/qKC}.

Baby Boi

Known to Kansas Citians today as a popular local DJ, Baby Boi’s first encounter with Soakie’s was also a pivotal moment in discovering their community.

Baby Boi recounts their teenage years, when they saw Soakie’s for the first time:

"A couple, you know, friends and I, we went to a haunted house‡. And of course, we're looking across the street, and we're like, what's up with that place? Because on the sign, you see 'Famous for Sandwiches' (laughs); but you see certain individuals walk in and they look a little different from so-called "everyday people." I wasn't old enough to really comprehend it.

When I got a little older, my friends and I would tell our parents we were going out to so-and-so's house, but really we would all sit in the parking lot across from Soakie's and look in awe."

It wouldn’t be that long before Baby Boi became part of the view. Baby Boi would be adopted into Kansas City’s Ballroom scene, and perform at Soakie’s under the pseudonym “Baby Beauty” of the House of Beauty§. Later on, Baby Boi would join the House of Carrington, where their role expanded into hosting shows and segments as well.

To my surprise, Baby Boi’s DJing career didn’t officially start until 2017–and it seems a perfect continuation from performing for, as Baby Boi puts it, “if [they] can give people a good time or experience, let’s do it.”

‡Baby Boi references the late-haunted house, Main Street Morgue: located on 1325 Main Street from the 1970s to the early 00s. The business was shut down as part of the Power & Light Development.

§Descriptions of Kansas City's Ballrooms Scene are purposely meant to be ambiguous as to protect a well kept tradition of Kansas City's Black queer community.

Starla Carr

Donor of the “starla_carr_collection” to {B/qKC}

Starla: Got my good side?

Nasir: Yeah. [chuckles]

N: So to start…

Can you just tell me what’s your name?

S: My name is Starla Carr.

N: Starla Carr.

And where are you from?

S: I’m originally from Cali,

uh West side.

I’m originally from.

Los Angeles and now I live in Kansas.

N: How long have you been living in Kansas?

S: More years than I care to admit to

probably a good 30 years.

I have come to love Kansas, um

especially small town life and I never thought I’d be this person, but

the older I get, the peacefulness, the friendliness,

I just I can’t see myself living in a big city ever again.

but as a kid, it was extremely frustrating

because it was exciting being in Cali, even

though it was dangerous and violent at times.

Like it was exciting, you know, and I got I

had a really great childhood as far as like I got to do a lot of stuff

I…

am frequency.

I’m a vibe.

I am I’m a lot of things.

but it’s hard to really quantify exactly

who I am because I’m still learning myself even now, at my big age. um

I

am very much about duality of a lot

of things because I’m an artist.

So there is the masculine

and feminine parts of me that

that duality that kind of bounce back and forth.

There is the artist in me that is creative

and and traumatized and

that bounces back and forth.

I am

there’s this new part

of me that is chronically ill, and so, and

then there’s a part of me that feels like I can do anything I want to do.

So there’s there’s a lot of duality

within me, but if I had to sum it up in one little sentence,

I just am frequency.

I knew I liked girls way back in, like, at seven or eight.

I had a crush on a girl at church school.

And we were like best friends.

And so she was come over to my house spend the night.

I would go to her house and I just thought she was just the most beautiful thing.

Like, I when I look back on it, I realized that that was a crush

and that wasn’t that was the

beginning, but I’ve always just loved women

in a way that it’s like, for me, is women are just everything, like,

not just the beauty or the romantic side of it, but

just the way we navigate the world, how

strong we are, like women are just

everything.

There was some conversation about Soakie’s being

a gay bar, and of course that made my little spidey

sensors tingle cause I was like “ooo, gay bar” um and

At this point, were you going to other gay bars?

I didn’t know of any others. Yeah, I didn’t know of any others.

I would eventually come to find out that there was a

couple of gay bars in Lawrence, Kansas and I

would also sneak there on my own and go a couple times.

but I didn’t know of any other place but what I

heard about Soakie’s and um it

was a friend of one of the guys

that I was in [a former rap group] with that was like yeah,

they have epic fights at Soakie’s.

and I was like what?

And he was like yeah, everybody just hits in the parking lot, watch the fight.

And I was like, okay, and

he and he was like I was like, let’s go.

And he’s like I’m not going to Soakie’s,

That’s a gay bar.

I was like, we could just sit outside and we don’t have to go inside.

and so we went and sat

outside for like a couple of hours and it

was, which we’ve come to unpack is ‘Parkin’ Lot Pimpin’’

is what they call it, but we like the parking lot

that was in front of Soakie’s was pretty big,

and we sat at the back we drove and parked our car

at the back of the parking lot and just sat and watched

people walking around in out the club wasn’t any fights going on.

It was just a normal night and

we just sat there looking at people and talking like the

whole couple of hours, but then I was like okay I got to get inside.

I got to get inside there.

And um

I had a friend at the time named Casey and Casey,

young lesbian, uh has dated

somebody who was coming to Soakie’s.

And so

I think she was the first person that took me

and and at this point I’ve been out for a few years.

I’m still trying to find my own as a

lesbian, like what does that mean to me?

and I’ve gone all the way from femme to masc

and I think and I’m

super comfortable as the masculine version of me.

And

plus I felt like which is weird to say, but

I felt like dating was easier as a masculine lesbian.

But anyway, we started coming to Soakie’s.

and then I found out by coming that uh they had entertainment.

And I was like, okay, this is cool.

Uh, I’ll never forget a shout out to

[Mama Mamie], and she’s gonna love to hear this, but Mama

Ma’ was uh she used to sell

food outside the club and there was a lot

of times she was our door person for Soakie’s and

her smile was so well–

warm and welcoming like we would chat outside

and, you know, about plates or whatever, and then there

was a store next door where they sold like sex supplies and what not.

and um she ended up working over there.

And so going in and out from bar to over

there, it was just like she became a familiar face to me and

definitely a comfortable comfortable person to talk to

and um very sweet, and uh we’re still friends to this day.

And she ended up also being a show director

at a different club which I performed at but um we formed a friendship. um

um I started dating at the club, uh

came into a long-term relationship with someone who was

entertainer there and um yeah,

and then when I got with who was now my ex when

I got with her, she was more established

as an entertainer theirs.

And as she was performing and

whatnot, it’s like we became the parents

of all of these younger uh gay

performers and entertainers.

And as you know, there’s different houses.

So she had her own house, the House of Beauty.

The weird thing is, and this is just a very me thing because I’m very much

I’m

very much the kind of person who gets along with everybody socially,

but I’ve never fit in a clique.

I’ve never fit in a group.

So I was never asked to be in any house, by the way.

but because I

was with her, by proxy, I was in the

House of Beauty because I was her girlfriend, even though

she never even asked me to be in the house, but I was in the House of Beauty and so

as a parent figure,

I really love that role.

I to this day, I still have

gay family that call me ‘unc’ or call me ‘pops’

or call me whatever, and I if it feels good,

it feels really good that they look at me like that, and

to be able to be that person you can come to for advice

or and that’s what I became in

that role was almost a masculine fatherlike

figure to a lot of queer young people.

And I think just because of the

nature of my personality, which is I’ve always had kind of an old soul, um

people started calling me up for advice for

what to do or how to handle a situation or what was going on in their personal life.

And I very much clung to that role as

well as an entertainer, but

that was important to me and all of that happened at Soakie’s.

Every person that I met came in contact

with had the honor privilege of performing

with or around, like all of those connections

came from going to Soakie’s.

Soakie’s was family. um

there there were so many people that

I had hard conversations with in the club

uh that

I needed to have conversations with people who understood me.

Um

There was dating.

There was romance. um

there was it was just

everything I needed to be in this little hole in the wall clubs,

like community um

we lost so many people and

we’d lose somebody and then we show up that night at the bar.

and you could be sloppy drunk or you could be

crying or you could be upset.

We always did benefit shows um when

someone passed and to try and raise money for the family, um

there… where else are you gonna do that?

You know what I mean?

Like I had I’ve never seen that habit in my life uh

where someone’s love one partner

spouse, whatever’s passed away,

and then this community comes together just

to give them money or perform for them.

And that was unique to me. um

there was real

hard situations um

of couples that broke up.

Like the thing about it is, Soakie’s on

the outside looking in, there was always this

perception of violence from people in the club.

There was

a perception from the outside looking in that

oh, the queers are out there doing whatever,

the drag fights and what not, but what they don’t understand is

when you come up

without support, without help,

without finance, you

end up in those kind of violent situations.

Like, I can talk about it maturely now as an adult,

but every single fight I ever saw was

real shit like this was not

little light hearted things.

This was I’ve been with this person for 13

years and were not together any more.

in in the straight world

a divorce, but we didn’t have words and language for that.

It was a break up.

It happened and everybody in the club knows that no longer

you with this person now you’re with this person and now people are big in sides and

yeah, it was violent.

It was raw.

It was real, but we it was still in an environment

where there was love.

It’s not going to look like anybody

else’s version of love, but

you knew there was safety and love there, and

yet there were fights, and yes, there

was drugs and there was everything else there just like the

real world, but we had family and

even like I’ll never forget this is a true story.

There was a

a pageant that we had, and when we had the pageant

we would open up the garage area next to Soakie’s so we had more room.

And there was a

group of straight guys, I’m assuming straight guys, I don’t know, that came to the club.

and um one of my

gay kids uh was going back

and forth between behind the stage and the dressing room.

um, one of my best friends who

was the DJ from my group who

wasn’t even gay, who was the DJ there that night.

uh, I saw one

of my kids walking past this guy who

was headed back towards the back dressing room,

and one of my gay kids, their spouse,

uh, was talking to some guy who

was trying to hit on her and I’m watching.

I’m sitting in the cut, and I’m watching.

and I see her actively like I

have somebody go away, and I see the aggression

level going up from this straight guy like you know,

“You aint gotta be with them”

and I see that my child, that’s how

I consider it, doesn’t see what’s coming, and

I just started making my way over just in case.

and the two

the couple went through the back way to

go back to the dressing room, did not see that this

guy was headed towards them.

Their backs were turned, and I stepped in between, and I was like that’s not what you want right there.

I need you to turn around and head on back the other way.

“Well, who are you?”

And by the time he said that

motions

it was like Gary, it was the DJ.

It was like

protection.

And they tossed him out.

But that’s what we did for each other.

And and it was

in the real world, you don’t have that protection.

If I’m walking down the street with my lover and we hold hands

or we kiss, Gary’s not gonna pop out or

somebody else, you know, bouncers that I love and care about.

They’re not gonna pop out and just be like, hey, leave them alone.

You know what I mean?

Like, so

it definitely was

something that I absolutely needed.

And the friendships,

um which have lasted well beyond the building,

um are still there.

We’re still there, so it was very deep.

I don’t I don’t even think some some

day maybe I’ll fully realize how deep it was because I’m still unpacking

uh a lot of the lessons that I learned there.

But yeah.

….that was Soakie’s.

Starla Carr’s “Queer Club Culture in 1990s Kansas City: A Chance Encounter with Soakies,” featured in the Hip Hop Dance Almanac, was a foundational piece for me in beginning this research project.

And just as she was foundational for me now, Starla has been a pivotal force in developing Kansas City’s drag king circuit over the past 30 years. Known under the performing name “MT” (and performing alongside Baby Boi on numerous occasions), Starla recounts her experience as a performer:

"Our male drag group was called the Kings of KC. The connections I made at Soakie's extended farther than just performing at the club, and I started to meet male drag artists all over Kansas City. Our Drag King group practiced routines in my living room preparing for shows, and one of my favorite memories is when we decided to perform a song by the Black Eyed Peas remixed with 'Love Shack' by The B-52's. It was stupid hot that summer, and we were wearing afro wigs for the first part of the performance, switching costumes when the song flipped [...] We transformed ourselves into our favorite rap artists and RnB singers. I still remember using spirit gum and weave clippings to make a fake little mustache for my performance as LL Cool J.

[...]

Soakie's had balls, too, much like those of the Harlem Renaissance era, and that's when we'd bring out the best performances. You were guaranteed to find top shelf entertainment, dance routines worked on for months and the newest music. As a member of the entertainers there, my eyes were opened to how society treated us outside the safety of our club, so I became a gatekeeper, making sure the place remained safe and it's a responsibility I don't take lightly."

Outside of performing at Soakie’s herself, Starla helped other entertainers by designing their costumes and choreographing their performances.

Above all, though, Starla has been an instrumental support system for those around her. Starla recounted stories about marrying one of her male best friends so he could keep his visa and holding space for gender non-conforming individuals who didn’t fit within binary systems at Soakie’s (and elsewhere).

It is with great honor that I welcome her collection to {B/qKC}.

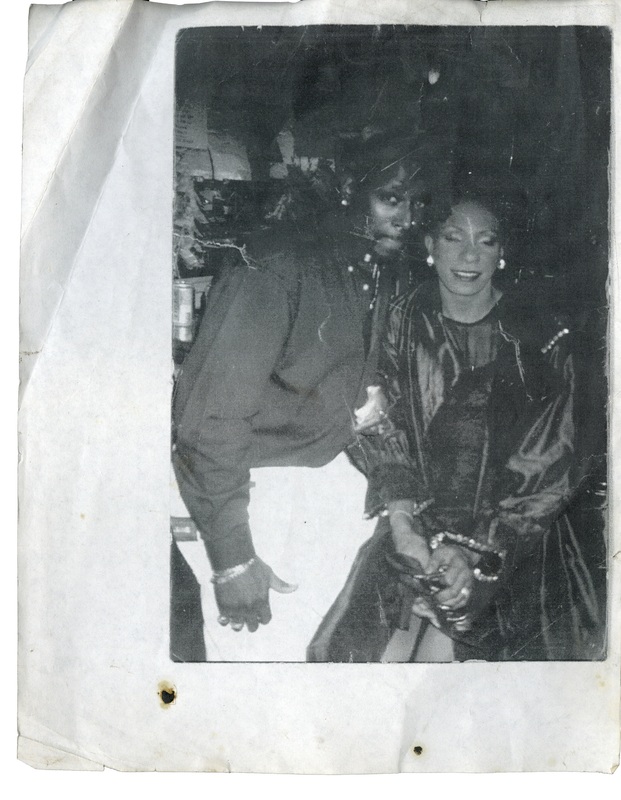

The "starla_carr_collection" is one of the inaugural collections digitized and donated to {B/qKC}. The collection consists of various photos from Carr's time as a seamstress, performer and go-er of Soakies in the early 2000s.

Tisha Taylor

Donor of the “Tisha Taylor Collection” to {B/qKC}

A photo of Tisha Taylor (center) printed in K.C. Exposures as part of Tisha Taylor’s Birthday Bash in 2004. On either side are the succeeding owners of Soakie’s (who are dually Salvatore’s nephew and niece-in-law): Jimmy (left) and Sue (right). (Photo by Chuck Tackett. “Tisha Taylor’s Birthday Bash,” KC Exposures. April 29, 2004. Digitized as part of the Gary Carrington Collection of {B/qKC}).

Tisha Taylor was an instrumental part in managing and ensuring Soakie’s success. Originally a “front-door girl,” or greeter, for the bar, Taylor’s role would expand after Jerry Colston was victim of a stabbing around the first year of Soakie’s opening. During his recovery, Taylor managed the bar: developing different events and entertainment and bringing in famous talent–such as porn star Bobby Blake one New Year’s Eve.

Taylor reflects on a New Year’s Eve 2000 party–one of her favorite memories from Soakie’s–below:

"Our New Year's Eve parties were eventful. Those, and then my birthday party as well, which were fun. I had birthday parties where I had cakes with fountains and bridges...they looked like wedding cakes. And people would come in and say, 'Who's getting married?' (laughs)

But there was one New Year's Eve party we were all scared because, you know, we were always told that in the year 2000 the lights were going to go out. The world was gonna end. And we all fed into that. So we all came together and did the countdown that year. And before the end of it, we said, well, you know, we don't know what's going on, but we're glad we're together.

So, all of us that hung out together, all of us, were in that one spot.

Outside of Soakie’s, Taylor has made a huge impact on the local Black LGBTQ+ scene, winning Miss Gay Kansas City America in 1995 and founding Kansas City’s annual Black Pride in 1999.

It is with great honor that I welcome her collection to {B/qKC}.

The “tisha_taylor_collection” is one of the inaugural collections digitized and donated to {B/qKC}. The collection consists of various photos from Taylor’s time at Soakie’s and Kansas City’s Black Pride in 1999.

Gary Carrington

Donor of the “gary_carrington_collection” to {B/qKC}

Montalvo: A test shot and some audio.

Can you say like something?

Carrington: Like…I mean

Be like, “Hi, my name is Gary.”

Hi, my name is Gary.

And where are you from?

Kansas City, Missouri. Born and raised.

Born and raised? Never left? Never went anywhere––

Um well, I lived outside of Kansas City for about three years when I was in St. Louis for school.

You know people talk about living, I’ve even talked about living

and moving somewhere else, but I’m I mean this is my city.

I love Kansas City.

I don’t think I would be happy living any place else.

I can go visit but, no.

This is home.

I’m boisterous.

It’s very rare that I don’t speak my mind.

I’m boldly, I’ve gotten

learned. how to be honest and transparent with people.

That was something I had to learn.

I did learn that.

But I’m very, I’m supportive.

Like I said, I’m honest, you know, I’m someone you

can if I say I’m gonna do something, then you can

best believe that it’s gonna get done.

I always stand by my word

Our gay community here in Kansas City, when

I came out, it was surrounded by a whole lot of

con artists.

And what I mean by that, it was a whole lot of, oh, I can help

you, oh, I can teach you, I can show you, but it was all based around sexual things.

So you had to be real leery

and real conscious about who you spent your time with and who you were getting to know

During that time, that’s when my

gay family really showed up for me.

That’s when they turned into my gay family.

Hey, don’t worry about it.

We got you.

And that’s when I started

realizing and seeing the the workings

of people who were outcast by their own family, but that

found each other and came together and built a family.

And we’ve been those people stayed my

friends to this day, so yeah, that’d be my family.

Who are the specific people?

Well one, my gay mom, they called her Mother Gooch.

She passed away.

She passed away in 2013.

Then there was uh my gay dad, which was Carver,

and he I think he passed away in

2018, 2019.

But they they were just together.

I mean, they didn’t live together.

They were just best friends.

And together as a group on a daily basis

they just showed me, well not just me, the group of people they

took in, like their kids, because Gooch was the type of person that

I was the only person there.

When I got to Gooch’s house, there were four other, you know,

males that she had took in, having the same

situation and she just raised us as a family, like

she was like he was really our mother, you know, hey, rules and

regulations, you know have to pay bills, you have to keep the house cleaned, stuff like that.

This, I’m assuming, is the House of Carrington?

or is it just a—

No.

At the time that this was forming, right as I was going off to school is

when the, I won’t say the Ball[room] scene, but when the family thing

was real popular and going around.

But when I got to the St.

Louis, we had never actually formed a family here.

So when I got to St. Louis and started hanging around those people

and that group of my St. Louis family, that’s when,

you know, one of my friends Sable, he was a female impersonator.

He was Sable Carrington, just said, “you’re going to be my son.”

And he said, as of right now your last name is Carrington.

And when I came back to Kansas City,

by then it already got around, “oh, Gary, Carrington, Gary Carrington, Gary Carrington.”

And that’s when I started the Carrington house here in Kansas City, that

I was the very first one here in Kansas City, and that’s when I started everybody else.

Okay, yeah,

You’re the Godfather.

I love that.

What was what was the scene like at that time, like were

you having fun, like going to the clubs and stuff, uh, were you having a good time?

I guess I was having a good time because, like I

said, they were teaching me a lot. and then in the gay family group, and

that they’re one of the things that were always teach us, it’s not

where you go, it’s the people you’re with.

So, of course, all the clubs back in those days were designed.

They were not designed for us.

You know, they didn’t play any of our music.

You know, of course they let us in, take our money, but it wasn’t designed for us.

So, as long as we stayed together with the people we

were with, of course, we had a good time because of the people I was with, not where was

not where I was at, it was the people I was with.

But back in the day, the clubs were very much adamant, you can tell, they were not designed for us.

That’s still how it is today. [laughs]

To this day! In 2025. To this day.

Because when Soakie’s–

Soakie’s became such a hot item. Soakie’s became that

little small space became such a major

foot in the gay community, but it was a foot in a Black gay community

Back then pre-partying was, you know, the big thing.

So let’s go here, have a couple of drinks, and then by the

time we get we having a couple of drinks here, everything will be ready to go. where we where we used to party at.

So we would go down to Soakie’s and stay down there for about maybe a couple

of hours or so, and then it started catching on.

The more and more people started coming.

And then Tish, Jerry started talking to

“Soakie” [Salvatore A. Rinaldo] about doing things down there.

And that’s when he found out he was like––

They said in order for them to get a 3 o’clock license,

They had their food revenue had to go up. because

I don’t know what it was, but they said, you know, they had them sell so much food

in order to get approved for three o’clock license.

So that was our goal.

So we did that.

We would tell people go down there for lunch. At night, we would go down there and buy sandwiches.

and we finally got the license.

And then that’s when that took off and we started like remodeling and taking, making, changes.

because the man was making money.

He didn’t have no problem.

He was an Italian, he was making money.

Sounds like he was pretty accepting to you all.

That he was.

Whatever we went and asked for him, whatever we went to him and said we

wanted to do or thought about doing, if it wasn’t a problem, he didn’t have any issue.

Like I said, we went in. He was this old Italian man.

These are Black gay people coming into your establishment.

I mean, you serve lunch, you know, to people who are––

you know, working in The Mob or whatever, you because that place was packed during lunch.

In Downtown, that was a place.

Businessmen down in your their their suits and making deals.

They’re sitting here eating hoagie sandwiches and drinking beer.

And now at night we want you to flip the script

and turn it into…he was very open

Hell, he remodeled the four times for us. He was very accepting.

Why do you think he was so willing

to change the the shop at night?

I believe it was Tisha [Taylor] and Jerry [Colston]

I believe whatever conversation they had––

And Eric [Robinson]?

Yeah, yeah. I believe whatever conversation they had, they convinced him to trust them.

And they within him trusting them, you

know, they brought us on. “Hey Gary, I need you, you know, to be a, you

know, to work the door for me” as those things started forming.

My little brother Danny, before he passed, “hey, Danny, I need you to be a bartender.”

And I think

they showed him what they could do and he trusted

them and then he realized, hey, I can trust these people.

Then it got to the point that [Soakie] wouldn’t even come in.

You know, he would, Soakie was usually there seven days a week.

It got to the point that he would show up on Fridays.

Fridays to write the checks and pay the bills for the liquor, and

pay everybody payroll and he leave everything to Jerry and Tisha.

What was it like, like, when Soakie’s

shut down, how did that impact you and the community and stuff?

When I got the call,

When Tisha called and said “hey, you need to come down and clear

out all yourself out of the dressing room because, you know, they’re not renewing our license, they’re shutting this down.”

This is right before they started out remodeling the Power & Light [District]

H&R Block, but we knew it was coming.

They were getting ready put us out of there because they were redoing Downtown.

it was a a blow, because we had been there, we put, and I

do mean blood sweat and tears, we had painted walls, we had made floors.

We had took out furniture.

We had you know, hung doors.

Our dressing room was an old storage room and we had to go in and hang

light and clean out and gut and redo just

so we have a place for the dressing room. so it was it was kind of bittersweet.

When we went down and we cleaned out the dressing room and took mementos.

I still have a bar stool from Soakie’s in my house right now.

[chuckles] I stole one of the bar stools.

So and we took mementos, and so like I thought it was bittersweet and

then it took us it took the community a minute to realize, okay, Soakie’s not here anymore.

It’s done.

What are we gonna do?

If we can get one person to say, hey, I want to open a business here

in Kansas City and I want to be a Black gay bar, that bar is going to make money because it’s a need.

It

it’s a need.

Because we’ can go into any bar in the city any and

they’re all, you know, catering to the our other counterparts, we

can have a drink with whatever, but it’s not gonna be for us.

It’s not designed for us.

You know, it’s not made for us.

You’ll take us in, but

I believe that’s what we need.

I just need one person to say, hey, I’m gonna open this bar.

And why is that so important?

Like, why was Soakie’s so important?

Like, why are bars for us so important, or important to you?

Well, important to me because it was basically our seat at the table.

It was our voice.

You know, at that time back in that era, everybody, you know,

first of all, gay wasn’t as out it is now,

wasn’t looked up on as it is now, so accepted.

Back then, so it was our place.

It was our place we could go and be us.

We didn’t have to put on any airs we didn’t have to, you know, conduct

us, we didn’t have to we could go and just be us, be open and free.

See, at the other bars, we have to, you know,

you know, the way we talk and joke and play with each other,

you know, they think we’re fighting, or they think there’s a problem or

issue, or you know, I can tell that

the drink I just ordered is not the same drink that you––

You understand what I’m saying? The service [was different]. And I sense that. And I just got tired of faking it.

And I think that’s what Soakie’s was. Soakie’s was our place.

Because a lot of people came to Soakie’s, and they never even went inside the bar.

They would come down park in the parking lot, pop their trunk, put

out their lawn chairs and their cooler and sit right there in the park because they were around their people.

They felt home that they they felt at home, so that’s where it was.

and that’s the need here in this community that

we, as a Black gay community, we need a place where we can say, hey, this is ours.

This is us.

A place where we can walk into a bar and see, you know, pictures of

entertainers that went to win national titles, that does such-and-such, and we don’t we don’t have that here.

We don’t have any place that honors or

respects or mentions, you know, anybody in our Black gay community

because we have no voice.

We have no place.

Gary Carrington, alongside Tisha Taylor, was instrumental in helping manage the bar. Carrington initially started out as security, checking ID’s at the door, but his role expanded during Jerry’s recovery. Taylor credits Carrington with creating the Mr. and Miss Soakie’s Pageant–and specifically creating a culture that allowed men to compete in pageant competitions similar to their drag queen counterparts.

Carrington was also one of the first men to entertain in the bar through emceeing Soakie’s competitions, though his introduction to the task was accidental. When Tisha Taylor changed costumes, she would task Carrington with entertaining the crowd. But he became enamored with the act:

"It's a bar full of people, listening to my every word while I hold the microphone. I loved it."

Taylor, who still texts Carrington every morning to check on him, had this to say:

"Gary was one of the first ones that started entertaining as far as emceeing. I was originally emcee, and then Gary started taking over as emcee.

And I always, you know, I pat myself on the back for Gary all the time because he was a product of me. (laughs)

But, Gary is himself. Gary is original. If I were to have something, he would be the first one I would call to emcee that because he's very entertaining. I don't even want to stand up next to him anymore. He puts me to shame. I go back to those days often.

Similar to Taylor’s sentiments, Carrington was not only instrumental in providing the photos and ephemera to make this article possible but a powerful link to other Black LGBTQ+ folks who used to attend Soakie’s.

It is with great honor that I welcome his collection to {B/qKC}.

The “gary_carrington_collection” is one of the inaugural collections digitized and donated to {B/qKC}. The collection consists of various photos from Carrington’s time at Soakie’s, as well as clippings from KC Exposures.

Closing Shift: Gentrification of Downtown Kansas City

Much of the reason Soakie’s no longer exists today was outside the control of its Black audience.

Around 2002, founder Salvatore Rinaldo died under mysterious circumstances–ruled a suicide, officially, by carbon monoxide poisoning.

After Rinaldo’s death, his nephew and niece, Jimmy and Sue, took over the bar, which led to a temporary break in Soakie’s as a nightclub.

Although they were successful in keeping the bar afloat, they faced a new challenge with the downtown Kansas City Power & Light (P&L) development project beginning in 2004–headed by the Cordish Company, an out-of-state, privately-held development organization responsible for the $850 million dollar development project. Cordish Company is responsible for the third- and fourth-wave gentrification that pushed out Black and low-income people to make way for P&L as we know it today10. This is also not the first time Cordish Companies has come under fire from the local queer community, having been met with protests in 2008 when Show Me Pride, LLC (the for-profit organization that commodified pride, created by the aforementioned John Koop) moved the annual Pride parade to P&L 11

According to several interviewees, the City of Kansas City had initially offered to buy out Soakie’s, but Jimmy and Sue refused their offer in hopes they would come back with something larger. To their dismay, however, the City expounded on Jimmy’s criminal background and served Jimmy an eviction notice after he was caught serving alcohol–unknowingly to Tisha Taylor12.

The night before the bar closed, a Sunday, there was one last large party. Around 9:00am later that day, Jimmy called Taylor and informed her the bar had been shut down, and he had already liquidated most of its belongings–thus, ending the sandwich bar and Black gay safehaven.

Conclusion

The LGBTQ+ community is suffering from a decline in Black gay bars and dedicated spaces for queer people of color. Though a bar may seem insignificant to some, Soakie’s demonstrates that the bar was more than just a place to have a drink. It was a nexus point. It was where people began to fully realize their identity. And, towards the end, it became a piece of political and economic organizing power against a development company.

Next year marks 30 years since Soakie’s was founded, and 20 years since it was shut down. I only pray that it does not take decades to build a Black queer sanctuary once again.

Top Row (L-R): Nykizha Iman, Tracy Carrington, Tremaine Scott, Nikita Carrington, Mocha Collins, Dovee Love

Middle Row: (L-R): Destiny Luv, China Collins, Treshawn Seymour, Lord Biskitt Carrington

Crouchers (Top to Bottom): Precious Seymour, Lady Kiesha, Lester

Bibliography

bahua. “Closed Bars and Restaurants.” Web log. KCRag Forum (blog). phpBB Forum Software, January 23, 2003. https://kcrag.com/viewtopic.php?t=10070&start=60.

Carr, Starla. “Queer Club Culture in 1990s Kansas City: Ink Cypher.” Hip-Hop Dance Almanac, May 2022. https://www.hiphopdancealmanac.com/ink-cypher-queer-club-culture.

Carrington-Balenciaga, Gee Gee (videographer), in private interview on Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023.

Colston, Jerry and Robinson, Eric (founders of Soakie’s as a Black gay bar), in private interview on Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023.

DeAngelo, Dory. MAIN STREET. 1999. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO. https://kchistory.org/image/main-street-7.

Jackson, David W. “Kansas City’s LGBTQIA Bar Census.” Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2016. https://libweb.umkc.edu/content/images/glama/timeline/jackson-book-bar-list.pdf.

Kelly, Korea (local historian and performer), in private interview on Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023.

Lovingood, Craig (also know as Drag Queen, Tisha Taylor), in private interview on Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023.

Martinez, Prince. “Who Are the Top Event/Party Promoters around the Country for QPOC? • Instinct Magazine.” Instinct Magazine, January 27, 2019. https://instinctmagazine.com/who-are-the-top-event-party-promoters-around-the-country-for-qpoc/.

Mattson, Greggor. “Are Gay Bars Closing? Using Business Listings to Infer Rates of Gay Bar Closure in the United States, 1977–2019.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5 (December 2019): 237802311989483. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119894832.

millerswiller. “Yup. Do you remember this nearby bar/’restaurant.’ Reddit. August, 10, 2016. https://www.reddit.com/r/kansascity/comments/4x0ze1/comment/d6byps2/

Montalvo, Nasir. “Men of All Colors Together: Fighting Racism amidst Gay Men in the 80’s.” Kansas City Defender, July 28, 2023. https://kansascitydefender.com/lgbtqia2/men-of-all-colors-together/.

Pinald/Norris. 1306-10 Main St Photo 1994. May 1994. Kansas City Historic Preservation Office. KANSAS CITY HISTORIC RESOURCES: SURVEY FORM.

Roland, Elara (known as DJ Baby Boi), in private interview on Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023.

Schiff, Barry. “Proficient Pilot: 300 Feet Per Mile.” AOPA, May 1, 2007. https://www.aopa.org/news-and-media/all-news/2007/may/01/proficient-pilot-(5).

Small, Karra. “New Kansas City Ordinance Allows Some Ex-Felons to Serve Liquor More Easily.” FOX 4 Kansas City WDAF-TV. December 7, 2018. https://fox4kc.com/news/new-kc-city-council-ordinance-allows-some-ex-felons-to-serve-liquor-more-easily/.

The Prideful Pony. “Big Gay Scandals.” Pride and its High Dollar Pony, June 22, 2010. https://queerkc.wordpress.com/category/big-gay-scandals/.

Thompson, Amy. “GENTRIFICATION THROUGH THE EYES (AND LENSES) OF KANSAS CITY RESIDENTS .” UM System, 2011. https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10355/14577/research.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

Footnotes

-

Greggor Mattson. “Are Gay Bars Closing? Using Business Listings to Infer Rates of Gay Bar Closure in the United States, 1977–2019.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5 (December 2019): 237802311989483. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119894832. ↩

-

millerswiller. “Yup. Do you remember this nearby bar/’restaurant.’ Reddit. August, 10, 2016. https://www.reddit.com/r/kansascity/comments/4x0ze1/comment/d6byps2/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3 ↩

-

Dory DeAngelo. MAIN STREET. 1999. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO. https://kchistory.org/image/main-street-7?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=4124fac5de772c67db87&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0. ↩

-

David W. Jackson. “Kansas City’s LGBTQIA Bar Census.” Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2016. ↩

-

Craig Lovingood (also known as Drag Queen Tisha Taylor), in a private interview about Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023. ↩

-

bahua. “Closed Bars and Restaurants.” Web log. KCRag Forum (blog). phpBB Forum Software, January 23, 2003. https://kcrag.com/viewtopic.php?t=10070&start=60. ↩

-

Nasir A. Montalvo. “Men of All Colors Together: Fighting Racism amidst Gay Men in the 80’s.” Kansas City Defender, July 28, 2023. https://kansascitydefender.com/lgbtqia2/men-of-all-colors-together/. ↩

-

Jerry Colston and Eric Robinson (founders of Soakie’s as a Black gay bar), in a private interview about Soakie’s, Kansas City, MO, 2023. ↩

-

Lovingood, interview. ↩

-

Amy Thompson, “GENTRIFICATION THROUGH THE EYES (AND LENSES) OF KANSAS CITY RESIDENTS ,” University of Missouri (dissertation, 2011), https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10355/14577/research.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y. ↩

-

The Prideful Pony. “Big Gay Scandals: Pride and its High Dollar Pony.” Queer Kansas City (blog), June 22, 2010. https://queerkc.wordpress.com/category/big-gay-scandals/. ↩

-

It is unclear whether Jimmy was convicted of a violent or non-violent criminal offense; Kansas City has had specific restrictions and jurisdictions around the handling of alcohol if a convicted felon. Small, Karra. “New Kansas City Ordinance Allows Some Ex-Felons to Serve Liquor More Easily.” FOX 4 Kansas City WDAF-TV. December 7, 2018. https://fox4kc.com/news/new-kc-city-council-ordinance-allows-some-ex-felons-to-serve-liquor-more-easily/. ↩